The article in the Rotarian describes Taylor Rapids, Wisconsin, as “snuggled down in the northern Wisconsin wood” and refers to it as not even a ghost settlement as nothing remains and the area has reverted to nature and forest.

Even the surest things, death and taxes, have vanished along with Taylor Rapids community, so complete has been its elimination. Its disappearance is due to the Badger State’s theory that it is better to go wild than to go broke.

Twenty years ago, when the boom was on to make an agricultural empire out of Wisconsin’s “slash” or cutover lands, Taylor Rapids, like score of other settlements, was self-sustaining. Hundreds of hard-working families, lured by the promise of rich land at a bargain, had put their life savings into the clearings, many of them locate at the end of dim forest trails.

But fate had stacked the cards against them. A crop or two, and the shallow soil faded out. Savings – what little they still had – were quickly dissipated. Taxes piled up. The future was black with despair. It was a case of move, starve, or do on relief. Realizing they were licked, many pulled stakes; others hung on in poverty and isolation.

Taylor Rapids community declined in population to seven families, six on relief, with no out-look for self-sustenance.

The article, written ten years after my Knapp family left in 1930 during the Great Depression, paints a picture of the dreadful living conditions of the area, and a surprisingly innovative lesson in state and county land management that we can all learn from today during this tough economic times.

Nothing Left Behind

As Wayne and Robert Knapp experienced on their 1967 trip back to Taylor Rapids, Wisconsin, and I and my mother experienced in 2006, nothing remains of the logging community and homesteads of our family. While not surprising as the area is a great distance from “civilization” and off the beaten path, for the past forty years, there has been quite a mystery around the why of Taylor Rapid’s disappearance. Thanks to Dan Giese, we now have a clearer picture of what happened.

According to the Rotarian article, it was just too costly to maintain Taylor Rapids as a viable community. While the dates are not clear, about the same time as the Knapp family were preparing to leave, the county sent in an auditor to uncover the real reasons behind the town’s drain on the county’s finances. He found that while Taylor Rapids was paying approximately $276 in taxes over a six year period, it was costing the county $21,602 for the same period.

The portrait the article paints of the area is sad. Many were promised viable land for farming left behind in the clear cut area by the loggers. It looked like rich, healthy soil, but it was shallow, good crops lasting for one or two years and then all the soil nutrition was gone. The sandy soil wouldn’t sustain much agriculture, for crops or animals.

Describing the benefits to the state and county for costs spent to accommodate those living so far from metropolitan services, the article also describes the living conditions many suffered under in Taylor Rapids.

Zoning has eased the tax situation. The road-and-school guaranty, plus relief to mendicants, kept many counties on the verge of bankruptcy. One county spent $1,200 to build a road into a squatter’s $300 clearing, and he used it just once – to travel out to Rhinelander, where he got a job in a factory. Another county spent $1,800 servicing one family for a year, although the total family investment in the county was less than $800. Another paid $4,000 for snow removal one season for a community of six families.

Where zoning is effective, rural slums – marked by shacks in which disease-breeding vermin hide, wells infected by outhouse near-by, primitive educational facilities, and an absence of medical and nursing care as well as religious and social life – have been almost wiped out. Cabins and shacks which once housed pioneers became the haven from year to year of squatters, who shift with the seasons. They moved, but communicable diseases remained. A mother died of typhoid in one of these shelters. A squatter family moved in the next season – in a month three of them were dead of typhoid. Such tragedies have spurred “slum clearance.” Counties have destroyed many tar-paper shanties, old logging camp bunkhouses, and other refuges, filled impure wells, burned obnoxious outhouses, sanitized premises, blocked old trails.

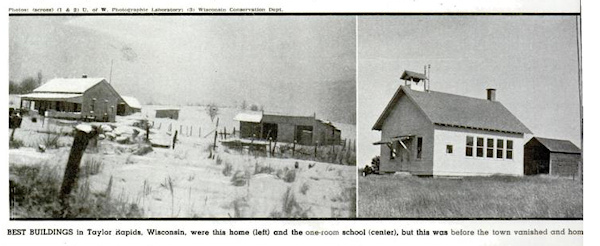

Rural-school standards have advanced. Instead of poverty-stricken little schools of four to ten pupils each, consolidated schools of 25 to 50 pupils each have become frequent – and at a much lower cost. A rural school with 30 or 40 children can be operated at a cost of $40 per pupil per year, while if there are six children or less, the expense may range up to $300 each, or even more, and with a fraction of the efficiency. In Three Lakes, one school serves six former districts, busses operating 20 miles to transport the children. Yet the expense is less although schooling has improved. Scores of isolated schools have been closed as a result of consolidation.

Forest fires have decreased, rangers say, through the elimination of squatters who, working alone clearing land, often were unable to control their brush and stump fires. Also needless deaths, inevitable to isolation – such as an old lady who was taken sick and died in remote cabin without a medical attention. Three days later a trapper found the husband helpless by her side. Snowplows cut a road part way to them. Then a man on snowshoes dragged a toboggan the last few miles to bring the body out for burial. Medical aid went in to the man.

The new principle has brought to the rural regions the idea of collective action toward Wisconsin’s goal – rural families on self-sustaining farms, accessible the year round, with mail, school, cream-route, and health service always available. It gives them opportunity for religious instruction and social intercourse as well as improved economic status. It paves the way for local government reorganization.

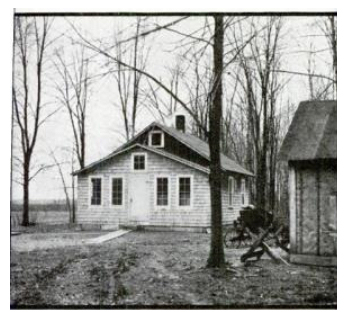

The article also includes photographs from Taylor Rapids, including a picture of the one-room school house where my grandfather, Raymond Anderson, taught, and where the Knapp children went to school, and where Seneca Primley, brother to Emma Primley Knapp, held church services.

The other buildings in the article might be ones discussed in the many stories by my great uncles, but without better identification we’re not sure.

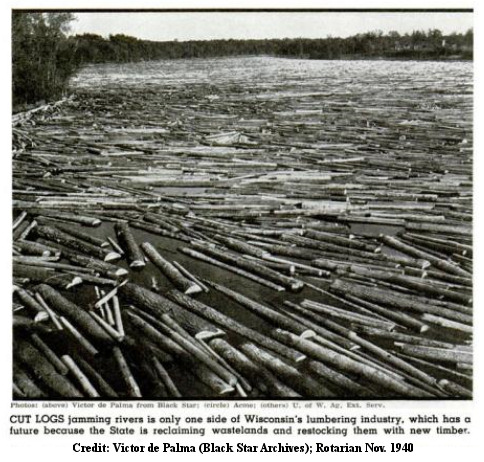

It also includes a dramatic perspective of Taylor Rapids in its logging heyday. The river crammed with logs in the article isn’t labeled, but it is very likely to be the Peshtigo River that passed Taylor Rapids. My great uncles described it as a rough but wide enough river in places that would transport the logs from the logging areas to the camps and transportation locations.

It also includes a dramatic perspective of Taylor Rapids in its logging heyday. The river crammed with logs in the article isn’t labeled, but it is very likely to be the Peshtigo River that passed Taylor Rapids. My great uncles described it as a rough but wide enough river in places that would transport the logs from the logging areas to the camps and transportation locations.

A County’s Ingenuity Leads to State-wide Benefits

Faced with the huge ever-growing deficit a community like Taylor Rapids was costing the county, they came up with a novel idea. Buy the land from them and pay for them to move to better lands and access to services. This gave the family hope and a boost in the right direction.

The county went out of their way to help, seeing the long term benefits over the short-term costs. As described above, by bringing people closer to services, they could lower their long term costs while preserving and restoring precious natural areas of the state for future use or just conservation purposes. Wisconsin law required access to a road and a school to every family, and bringing these remote communities closer to road access and schools minimized the costs of providing them.

The county went out of their way to help, seeing the long term benefits over the short-term costs. As described above, by bringing people closer to services, they could lower their long term costs while preserving and restoring precious natural areas of the state for future use or just conservation purposes. Wisconsin law required access to a road and a school to every family, and bringing these remote communities closer to road access and schools minimized the costs of providing them.

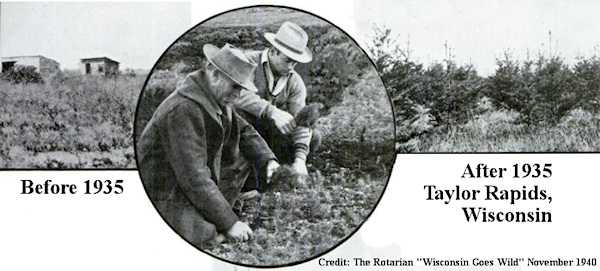

In eight years, one-seventh of the entire area of Wisconsin – “more than all of Massachusetts” – totaling five million areas, was acquired by the county and state. Most of these were by tax delinquencies and abandonment, or bought by purchase or trade, like the Knapp family properties leased from the Goodman Lumber Company. Some areas were set aside for sports and recreational activities, but the vast majority of the land was replanted or left to recover on its own.

The article calls this Wisconsin’s weapon of attack against the drain on its resources as well as advanced thinking in preservation and conservation all around.

A unique zoning law – an adaptation of the familiar city plan of property restriction – is Wisconsin’s weapon of attack. The first State to adopt such an act, it permits, but does not compel, counties to regulate and restrict their land to forestry, agriculture. and recreation.

…It proposed that county boards of supervisors be given right through the enactment of county zoning ordinances to “regulate, restrict, and determine the areas within which agriculture, forestry, and recreation may be conducted.”

In 1923, Wisconsin had passed a law enabling counties to zone land next to cities so that the suburban development might be harmonious with the metropolitan. In 1929, by simply amending that law so counties could segregate land for farming and non farming purposes, rural zoning on a comprehensive scale became legal.

These actions weren’t taken in a vacuum. The county consulted with the Wisconsin Conservation Commission, College of Agriculture of the University of Wisconsin, and with their constituents. According to the article, seventeen public meetings were held throughout the county to explain the zoning changes and the rights of the people to keep their land or take advantage of the chance to relocate. “All was done on a democratic basis – no pressure was applied, no orders were handed down from above. It was the will of the people, expressed 24 to 1.”

Over the next five years, twenty-three counties enacted the same procedures, finding tremendous support from within their own communities.

…they had not raised a bar against new settlers. In fact, it encouraged them. It kept them from being victimized by the purchase of barren isolated land and guided them to the 3 million acres of productive land in the 24 counties still open to settlement – enough land, according to University of Wisconsin – to take care of all expected newcomers for the next 50 to 75 years.

A side benefit to this action was a temporary increase in jobs. Thousands of people were hired to clean up the land, removing the old buildings, tearing up railroads, and restoring the land. Others build recreational and sporting facilities to suppport those who would soon return to hunt and fish, or just to enjoy the unique beauty of the area. As we witnessed, 20 years later the entire area around Taylor Rapids had been returned to nature, with nothing left standing save the trees.

Today’s states and counties are suffering greatly from the economic downturn. Wisconsin at the turn of the previous century serves as an example for others to follow. They looked at the costs to maintain those living in remote areas with little hope of economic benefit and found a creative way to not just help them but themselves in the process, saving millions of dollars while protecting their natural areas. We need some of that creative thinking today.

For our family, we now have a better picture of how and why Taylor Rapids disappeared from the map. While we’ve joked for decades about the Knapp family being the last to turn out the lights and leave Taylor Rapids and logging in northern Wisconsin, it turns out that this is more fact than fiction.

Most Recent Articles by Lorelle VanFossen

- The Myths and Mysteries and Hunt for Nicholas Knapp

- The Perpetual Calendar

- GenSmarts: Reminder to Not Assume

- Gensmarts Saves Your Family History Research Life

- Digging Through Historical Newspapers Online

Pingback: Scrivener: The Research Binder | Writers in the Grove