The following story by Robert Knapp (1913-1994) was written as part of a creative writing class. It highlights the rough life and work of towing logs on the Skagit River in Washington State during the 1930-1950s. People mentioned include Captain Charles Elwell (captain and pilot of The Skagit Chief tug boat), Otto Ellingsworth (engineer), Herby Camm (deck hand), and Joe Parker.

During the early thirties, I took a job cooking on a fifty foot tug boat, named The Skagit Chief. Captain Charles Elwell was the pilot. It was he who had got me the job. He was also my wife’s father. We towed logs from the upper Skagit River, near Marblemount, down river as far as Mount Vernon, Washington.

During the early thirties, I took a job cooking on a fifty foot tug boat, named The Skagit Chief. Captain Charles Elwell was the pilot. It was he who had got me the job. He was also my wife’s father. We towed logs from the upper Skagit River, near Marblemount, down river as far as Mount Vernon, Washington.

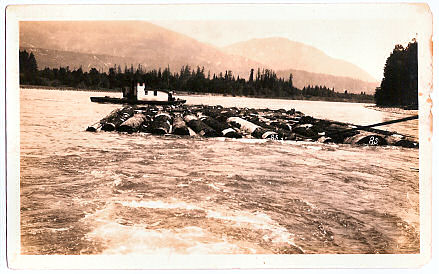

The logs were in sections tied together, making up a tow of fifteen or twenty sections. These long tows were taken across Puget Sound to Seattle and other points.

The logs were towed in rafts of two sections, as far as Mount Vernon. It was impossible to bring more than two sections at a time from the upper river. Each section was perhaps two hundred feet long, and about half that wide. They were held in place by boom sticks. Each section held close to a half million feet of logs. The boom sticks were laid fore and aft on each side of the rafts. Boom sticks were also across the front of the tow and back. Long heavy cables were stretched across the tows holding them together.

Boom Sticks, as they were called, were extra long logs with three inch holes bored in each end. They were held together with boom were chains. The heavy boom chains were perhaps eight or ten feet in length. They had a ring in one end and a bar in the other. The bar went through the hole in the stick, looping another, and back through the ring.

Boom Sticks, as they were called, were extra long logs with three inch holes bored in each end. They were held together with boom were chains. The heavy boom chains were perhaps eight or ten feet in length. They had a ring in one end and a bar in the other. The bar went through the hole in the stick, looping another, and back through the ring.

The bridle, was two cables with a ring in the center. The cables were shackled to each corner of the front of the tow. The tow rope was made fast to the ring in the center. The tow line was made of Manila hemp, two inches in diameter. At that time it was the best rope that money could buy. It was fastened to the bitts at the stern of the tug.

The bitts were two hardwood posts that were anchored and braced from the bottom of the tug, up through the deck. They were usually made of Yew Wood, perhaps ten inches in diameter. They sat side by side about three feet apart, with a cross piece between.

The tug had two sixty horse V8 engines for power. They were situated in the galley, just back of the table where the crew ate their meals. The noise from those roaring engines was difficult to get used to. The bunks where we slept located above the engines and a little to one side.

The engines made so much noise I thought I would never be able get any sleep. But after the first few sleepless nights, I got over the noise. I was able to sleep as soundly as the next one.

There was always a bucket of paint handy. When there was spare time, it was my job to paint wherever it was needed. The old tug was always in need of, paint in one place or another. There was little wasted time actually waisted. When we would go home once or twice a month, found it hard to go to sleep. I missed the roar of those sixty horse engines.

Coffee was kept hot day and night. Gallons of the black stuff was consumed on those long slow trips up river. The trip up river took from eight to ten hours. Coming down with the tow took about half the time. It was a breath taking job at times.

There were usually four men to cook for including myself. The Captain, Charles Elwell, the engineer, Otto Ellingsworth, the deck hand, Herby Camm, and me.

Otto Ellingsworth was crippled. He was a blacksmith by trade, but he understood engines so well that he was hired to be engineer on the boat. Besides that he was a good friend of the owner of the boat, Joe Parker of Mount Vernon. Otto was a good natured fellow with a great sense of humor. He seldom showed any type of anger. An injury to his back many years before caused him to walk stooped over, he resembled a large spider. But believe me he could get around better than most people could without an injury. After a few trips, the boat owner installed controls from the pilot house, and Otto was no longer needed for the job he had held. We all missed Otto, he was the life of the crew, always ready for a laugh, or a story. After he left the tug boat, he went back to his blacksmith shop in Mount-Vernon.

The Dells

Some of the places along the river were rough, and difficult to navigate. The dells was the most dangerous place along the route. This was where the main channel of the stream ran directly into a rock wall.

This huge rock wall was much like the side of a mountain. It jutted out into the channel, far enough to hook the raft of logs. If the tug wasn’t handled just right, the tow could easily be torn apart, permitting logs to escape from under the boom sticks.

The current was extremely swift at this point. It also made a sharp turn to the right away from the wall. This was one of the most dreaded spots to all hands on deck. The tow would smash into this wall with a tremendous force. Captain Elwell had never lost log at this place, due to his vast experience, in and his sound ability in handling the boat.

About a half a mile before getting to the Dells, a heavy drag chain was fastened to the rear of the tow. This was to keep the tow from traveling with the speed of the current. It also helped to prevent the tow from pounding so hard at the dells. The chain helped a little, but it took some really fine maneuvering to keep the tow and tug in control at this point. If the drag chain happened to get hung up on the rocky bottom and break loose from the tow, were in trouble. However, this never happened while I was on the job. I understood that it had occurred in the past, but not often.

After getting past the dells, the drag chain was no longer needed. The tow was shoved into the bank, and the drag chain was pulled on deck with the power of a capstain at the bow of the boat. The chain was over a hundred feet long. With each link about three inches, and three eighths of an inch thick. It had to he wrapped around the cabin where it was kept till the next trip. The chain only lasted a short time. Dragging on that river bottom soon wore it out. Then it was discarded, and a new one put on.

Log towing was only done when the river was at flood stage. This was also a dangerous time. The river was full of drifting objects. As we only went up river during the night time, floating debris had to be carefully watched for. Whole trees, stumps, as well as logs, and even live stock floated down stream. I was often amazed at the way Captain Elwell was able to pick out these objects on the darkest nights. He had a powerful search light, but seldom used it.

One dark night he called me to come up in the pilot house. It was up a short stairway of about four steps out of the galley, which didn’t take me long to get there. He said, “Robert, do you see that big stump comin’?”

I looked for all I was worth. I couldn’t see a blasted thing. I told him, “No, I don’t see anything but blackness.”

The old fellow then laughed, as he took deep puffs on his little black pipe. In just a very short time I was shocked to see a huge cedar stump, the size of an automobile drift by us close enough to be touched with my hand!

After a few of the kind of experience, I realised that the man was truly amazing. He could actually see in the dark. The long years of tug boating had taught him everything there was to know about the business. I know that after that I always slept much better.

Bridges on the Skagit River

Coming down river was great if things went well. Bridges that crossed the river were sometimes a problem. Some of the supports that held up the bridge didn’t allow much more than just room enough for the tow to pass through. In other words the tug had to be handled just so, as in some places only a couple of feet separated the tow from those supports. I don’t know what the outcome would have been, had the tow ever collided with those supports. It would have been a disaster either to the tow, or the bridge, or maybe both!

I recall one time we were towing a bunch of boom sticks from some place, I forgot where. Anyway it was early in the morning. We came to a bridge that had to be opened for us to pass through. When we got to the right distance from it, the Captain blew the whistle. This was a signal for the bridge tender to open the bridge!

When we got a little closer, he blew it again, but no bridge tender showed! The whistle look as if there loud’, it could be heard for a mile. It didn’t look as if there was going to be any one around to open the bridge. The captain gave orders to free the tow. Then he swung the boat about, heading back away from the low bridge, allowing the tow of sticks to pass through safely.

After several 5 repeated whistle blasts, we saw the tender running from his shack with his pants half up. He must have been sound asleep not to have heard that screaming blast of a whistle. Any way he did double time in opening the bridge, and we went on through!

The captain had chewed the stem off his pipe during the act, so you must know he was some what worried. After things settled down, and we got back to going again, I asked the captain what happened to the stem of his pipe. He answered, “Gawd, I don’t know, I guess I must have swallered the blamed thing!”

We all got a laugh out of that, but it wasn’t so funny to begin with. It was necessary to report the bridge tenders lack of attention to the proper authorities. He was given a very serious reprimand.

Most Recent Articles by Robert F. Knapp (1913-1994)

- Poem: Evenin' by Robert Knapp

- Poem: The Little Kids (Robert and Wayne Knapp)

- Knapp Family: Our Introduction to the West in 1930

- Poem: The Good and the Bad by Robert Knapp

- The 1967 Trip Back to Taylor Rapids, Wisconsin

8 Responses to Towing Logs On The Skagit River